#ShotOnFilm by Abe // Boyle Heights, California 2024

President Trump started his second term exactly where he left off in 2021, waging an everyday psychological and physical war on immigrants. Joe Biden’s Presidential term was no help because he continued Trump’s immigration policies and did not provide a pathway to citizenship as he had campaigned, abandoning an estimated 11 million undocumented immigrants to their fate under the more openly fascist Trump regime. As a result, it has brought more attention to our undocumented community and our immigration policies.

The tug and pull by Democrats and Republicans of whether immigrants should have some rights to a dignified life has left us with a dysfunctional, incoherent immigration system for working-class people to understand, leaving people lost in how our system works or should work.

Consulting history reveals that our government does not work for the people; it works for the ruling class, the capitalist class. This is their system, not ours. We are conditioned to believe what politicians tell us, that we need to repeatedly vote for the next “good” candidate, which leaves us disappointed each time. In reality, we should challenge the system as a whole and its treatment of our most vulnerable community members.

Trump’s racist agenda against immigrants is nothing new. Trump is not an outsider who landed in the U.S. from Mars a few years ago and suddenly started attacking our people with hateful rhetoric and executive orders. Trump is homegrown and falls in line with all U.S. presidents before him in attacking our immigrant community. From the colonial period to the “founding” of this country to today, immigration law is rooted in racism. Therefore, Trump is following in the footsteps of his predecessors, Democrat or Republican, because the system allows him to do so.

Capitalism and Immigration

In capitalism’s eyes, immigrants are not regarded as humans but rather as a labor pool from which to extract maximum profit while also denying them basic human needs for a dignified life. This leaves migrant workers in fear, preventing them from demanding better wages or working conditions, as they live in a state of irregularity and vulnerability, facing the threat of unemployment, arrest, or worse, deportation. Undocumented workers from the Global South are essential to maximizing profits in wealthy, developed countries.

Migrant workers accept low wages and work in unhealthy, dangerous conditions, meaning that they are not free to choose where they want to work; they are pulled by capital. Therefore, the labor force exploited by the ruling class is central to creating value in the capitalist system.

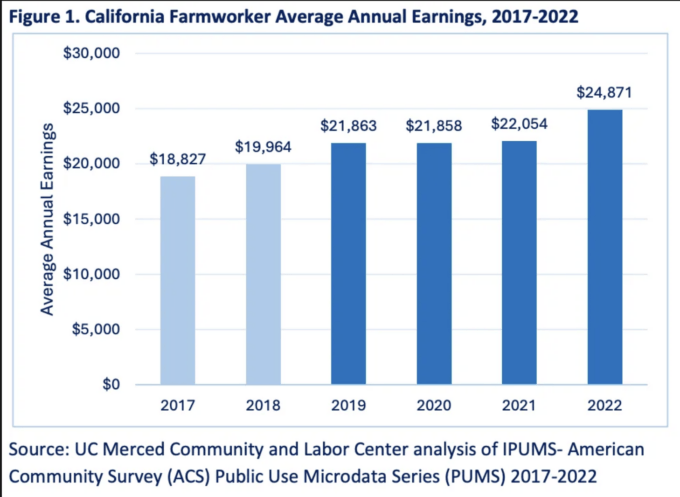

Moreover, capitalism does not set a specific price on goods we need or use; instead, it aims to maximize profit from what is produced and minimize the cost of labor involved. For example, in 2022, California’s agriculture sector generated more than $59 billion in sales, and the state remains a top producer of agricultural products in the nation, ranking as the world’s fifth-largest producer, surpassing the economies of many countries.

Meanwhile, farmworkers are among the most exploited workers in the country, earning about $24,871 annually, according to the UC Merced Community and Labor Center. There are approximately 500,000 to 800,000 farmworkers in California, with seventy-five percent being undocumented. In addition, “around 30% of households with farmworkers’ income fall below the poverty line, and 73% earn less than 200% of poverty (a threshold used in many public assistance programs),” reads a report by La Cooperativa.

In Trump’s first five months, he applied intense pressure on our undocumented communities. However, the capitalist class that relies on that labor pushed back against Trump, as the same individuals that ICE is targeting are those the system exploits, working in our fields, hotels, and the service industry.

For example, on April 10th, President Trump recommended at a Cabinet meeting, “We have to take care of our farmers, the hotels and, you know, the various places where they tend to, where they tend to need people.”

Industry leaders and Wall Street are well aware of the financial losses that would happen if the deportation system continues, and the U.S. economy could collapse in days if it succeeds in its plan to deport millions of undocumented workers.

“America currently faces a workforce shortage of 1.7 million people. We simply don’t have enough workers to fill the current job openings, and mass deportations could exacerbate this shortage and put further pressure on businesses,” said Sam Sanchez, owner of Third Coast Hospitality, National Restaurant Association board member, and co-chair of Comité de 100.

To clarify, what Sam is referring to regarding the 1.7 million workforce shortage is not a lack of unemployed people but rather a scarcity of individuals willing to take the low-wage jobs in the hospitality industry, where undocumented workers are often valued because industry owners can pay them low wages without providing benefits.

There are over six million documented unemployed people in the U.S., but many documented workers are unwilling to do this brutal work for low pay.

Since the founding of the U.S., immigration law has never truly reflected the needs of the people but has always served the interests of the ruling class. The labor pool of undocumented workers is like a faucet: when they are needed, entry is allowed; once the work is done, the outlet is tightened to deport them.

The Colonial Period to the Creation of the U.S.

In March, the Trump administration deported 252 people, mainly from Venezuela, to El Salvador’s torture camps, where they will be forced to work. This move resembles what previous empires did in the 18th century. In 1717, the Transportation Act enabled the British government to send convicts to its colonies, where they would be converted into indentured servants.

“Before the American Revolution, Britain transported about 50,000 convicts to the American colonies.”

Convicts, who later became indentured servants, were not the largest group of people forced into British colonies that eventually became the U.S.; instead, enslaved Africans were. Over 300,000 enslaved people were brought into North America. Slavery represented a different form of forced migration because, unlike convicts, enslaved people had no possibility of earning their freedom. Enslaved people and their descendants made up a significant portion of the population in British colonies and the U.S. since the 1600s.

Enslaved people were not viewed as immigrants because they faced an experience so torturously different that the story of slavery does not fit into the narrative of migration. Meanwhile, although enslaved people were never granted freedom on North American soil, convicts sent to the colony who became indentured servants eventually gained their freedom after years of forced labor; they were discharged with a small amount of cash, perhaps some land in a new continent, and skills to survive.

Settlers who left Britain for their colonies in North America did so of their own will because they were drawn by the possibility of purchasing cheap land taken from the Indigenous, high wages, and freedom from the King. Many of those people financed their voyage to North America. Settlers are not immigrants.

The Formation of Laws Around Citizenship

In 1790, the U.S. Census, which excluded Native Americans, showed that the population in the U.S. reached 3.9 million people. Additionally, the Census revealed that over 80 percent of the population identified as white. The same year, the U.S. passed its first citizenship law, the 1790 Naturalization Act. This law granted citizenship to “free white persons” who lived in the country for two continuous years.

People of European descent who were propertyless and indentured servants were not considered “free”; thus, gaining citizenship was restricted. White male suffrage was achieved on a state-by-state basis, and the law excluded non-whites, indentured servants, and enslaved people from naturalization.

The Soviet Union was the first country in the world to successfully create new educational and economic opportunities for women. In 1917, the Bolshevik legislative initiatives granted them full civil and political rights, while new laws ensured women were legally equal to men.

Meanwhile, white women in the U.S. did not secure the right to vote until 1920, one hundred forty years after the U.S.’s “founding.” Their right to vote emerged from an intense struggle that mobilized thousands of white women to challenge a system that didn’t acknowledge their civil and political interests. On the contrary, Black women were not allowed to vote until the Voting Rights Act of 1965, one hundred and eighty-nine years after the creation of the U.S., which also came after decades of sacrifice, organizing, and struggle.

In addition, when the country was formed, Black people of African descent did not have any rights, whether they were freed or enslaved people; citizenship rights were not extended to them, and that policy was upheld in the 1857 Dred Scott Supreme Court decision. The case stated that people of African descent were “beings of an inferior order” and were not allowed to become citizens.

However, Congress feared that a significant portion of the foreign-born population with voting rights could threaten national security, particularly with the possibility of going to war. Consequently, Congress passed the Naturalization Act of 1795, which extended the residency requirement to five years. It also included a clause stating that a potential citizen could declare their intention to naturalize three years before doing so. Notably, the 1795 act incorporated a religious component, changing the requirement from “good character” to “good moral character.”

During the late 1700s, war between the U.S. and France was possible. As a result, Congress passed a series of bills. In 1798, they passed the Alien Enemies Act, which extended the federal government’s power in immigration policy. Notably, it gave then-President John Adams the power to invoke the act to imprison and deport non-citizens during times of war or invasion.

Today, we are seeing Trump use this language that allows him to deport people from Venezuela with no legal pushback because he is calling it an “invasion” and claiming that they are “unlawfully infiltrating” the country. That is not true.

However, these laws increased the residency period for naturalization to 14 years and required individuals to declare their intention to naturalize 5 years prior. The waiting period was reduced to five years in 1802.

The U.S. Civil War ended in 1868, giving rise to the 14th Amendment, which primarily grants citizenship to all persons born or naturalized in the U.S. The amendment expanded the right of citizenship to formerly enslaved individuals and all people born on U.S. soil. Two years later, in 1870, the Nationality Act broadened these rights to include “persons of African nativity or descent.”

Native Americans born on tribal lands were not granted the citizenship rights that the Fourteenth Amendment guaranteed. Throughout the 18th and 19th centuries, they fought with determination for survival and sovereignty against U.S. expansionism and the doctrine of Manifest Destiny. (Similar to how Israel is colonizing Palestine, using religion as a land deed.)

In 1924, the U.S. finally granted Native Americans citizenship through the Indian Citizenship Act of 1924. Before the bill, only some Native Americans were granted citizenship if they joined the military, received land allotments, or were granted citizenship through treaties. The 1924 bill aimed to grant citizenship to all non-citizen Native Americans born in the U.S.

The Mexican Problem

While U.S. settlers used Manifest Destiny to exterminate the indigenous population as they expanded westward, another significant population was the Mexican people, who were forcibly incorporated into the country by the U.S. war of aggression that took fifty-five percent of Mexico. The U.S. and its forces conquered a large portion of Mexican territory during the Mexican-American War from 1846 to 1848, acquiring what are now the U.S. states of Utah, Nevada, California, Wyoming, New Mexico, Colorado, and Arizona.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo was signed on February 2, 1848. It stated that Mexican individuals who remained in the area of those states for one more year would automatically become U.S. citizens. However, like all U.S. treaties with Indigenous peoples, the U.S. government systematically violated this agreement.

With the U.S. government being the new overseers of the new territory in the Southwest, new struggles emerged for the indigenous people, revealing Congress’s racism.

The white-dominant society portrayed Mexicans as biologically inferior. Therefore, the fact that Mexicans from the Southwest could be naturalized under the Treaty of Guadalupe-Hidalgo posed a threat to white-only citizenship. Because of the U.S. conquest of the new territory, it was nearly impossible to remove them on a legal basis, and therefore, they faced new racist challenges. What came next was a racist media campaign against Mexicans.

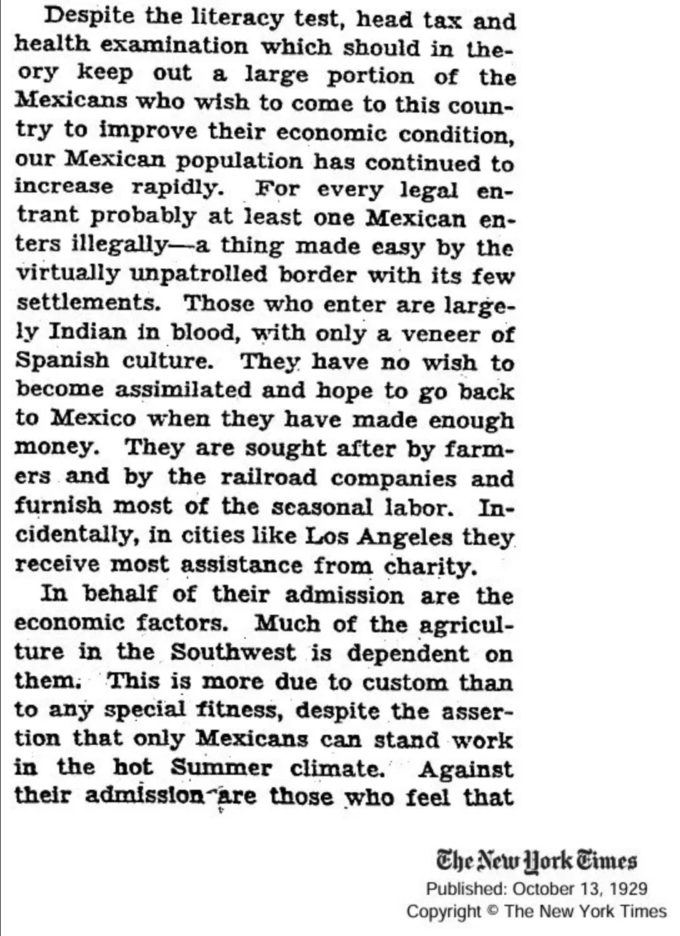

New York Times Article published October 13, 1929 // Source: New York Times Archives

Many Mexican workers found employment in agriculture across the Southwest. However, from 1900 to 1909, Mexican immigration was low, comprising only .6 percent of the total immigration to the U.S. Different class interests disputed their future. Congress denied Mexicans in the Southwest their voting and workers’ rights. Simultaneously, growers and business developers depended on exploiting their labor for profit. They testified before Congress about the value of their Mexican workers, effectively stalling restrictive legislation.

Between 1910 and the 1920s, Mexican migration increased as Chinese and Japanese agricultural workers departed, and people fleeing violence during the Mexican Revolution sought stability and employment. However, during the next decade, the demand for their labor declined with the start of the Great Depression. What followed was a campaign by the Border Patrol to detain Mexicans, which also included U.S.-born citizens, and deport them across the border—something that Trump mentioned on July 1st, stating he plans to do next: deport U.S.-born citizens.

When the U.S. entered World War II, it renewed efforts to recruit Mexican workers for wartime production, once again opening the faucet to keep the system operating.

The 1924 Immigration Act helped growers prevent Congress from passing more restrictive laws because it did not set quotas on the number of immigrants from the Western Hemisphere who could enter the United States. During this time, politicians and the press began, much like today, to inflame anti-Mexican and anti-immigrant sentiments. For four years, from 1926 to 1930, Congressmen attempted to expand the quotas to include Mexico and the entire Western Hemisphere.

The issue of what to do with Mexicans in the Southwest was such a concern for Congress that they placed the “Mexican problem” on their agenda. Thus, instead of providing a humane pathway to live in the U.S., they sought ways to remove them and treat them as second-class citizens in their ancestral land.

The Mexican people have endured systemic violence from the U.S. ruling class in various forms to strip away their political and labor rights since their land was taken by force one hundred and seventy-seven years ago. They’ve whipped up racist campaigns to stigmatize Mexicans as “illegal” or “alien” people. Unlike other immigrant groups in the U.S., a large portion of the Mexican people came under U.S. rule as a result of U.S. Imperialism.

Since then, the Mexican community has been systematically and consistently denied political rights and has struggled for better working conditions and equality at every turn.

In the 1950s, during an economic boom fueled by the Bracero program, millions of Mexicans migrated to the U.S. as “guest workers” from 1942 to 1964. The U.S. government organized a racist “operation wetback” that led to the deportation of over 1 million undocumented immigrants. Deportation as a tactic to further divide and conquer the Mexican people is now a multibillion-dollar industry that extends beyond the people of Mexico. Today, approximately forty-three percent of people detained by ICE are from El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras, according to data from the American Immigration Council.

In contrast, over 200,000 European immigrants were able to overturn their legal status between 1925 and 1965. In other words, Mexicans were brought in to work the fields in their ancestral lands, only to be deported after the growers exploited their labor.

‘Undesirable’ Countries and the Quota System

The Immigration Act of 1924 (The Johnson-Reed Act) limited the number of immigrants allowed into the country through a national origins quota. The quota permitted immigration visas to two percent of the total number of individuals of each nationality in the U.S., as recorded in the 1890 national census. It completely excluded immigrants from Asia.

By establishing a hierarchy among European peoples, the 1924 Immigration Act also underscored a notion of nationality that excluded non-white individuals. A minimal quota was set for individuals from African countries, and several countries were considered “ineligible for citizenship,” including those from various parts of Asia, such as Japan, Thailand, and India.

The 1924 Immigration Act excluded Asians from citizenship, particularly the Japanese, who were not previously barred from immigrating but were now admitted to the U.S. This set of laws upset Japanese officials, as it violated the Gentlemen’s Agreement. Despite the tension between the two nations, Congress was more concerned with preserving the nation’s racial composition than promoting good diplomacy with Japan.

The American Industrial Revolution and Immigration

The period from the 1850s to the 1900s was an era of industrialization in the U.S., a time of urbanization and immigration that propelled the nation toward developing its infrastructure and high-tech industries. During the Industrial Revolution, a significant wave of immigration occurred, transforming societies and economies worldwide. People sought economic opportunities, escaped violence, or had no choice but to leave their homeland, resulting in a massive demographic shift and cultural changes in both the sending and receiving countries. Those who welcomed a large influx of immigrants witnessed their economy and development flourish, while those who lost their indigenous populations struggled to recover economically.

The 19th century introduced new techniques and technologies that revolutionized the capitalist economy into a fully-fledged industrial profit-making system. The foundations of the new economy rested on the country’s westward expansion, which involved taking land from the indigenous people and developing railroads and factories across the nation, enabling the establishment of goods and services in the new territory.

The new projects peppered across the country required cheap labor willing to do the most brutal and dangerous manual labor jobs. A large portion of workers were from China, who were escaping colonialism and all its manifestations, like famine and violence. Chinese workers built enormous tracts of the U.S. railroad system, specifically in the West. As the California Gold Rush declined, so did the demand for cheap labor.

The pool of immigrant Chinese workers competed with white workers for survival. This led to the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act, which barred new Chinese workers from entering the U.S. Those already on U.S. soil were also ineligible for citizenship. The act expanded to include all Asian people except those from Japan.

It was not until 1898 that birthright citizenship was established in the United States.

The 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act was the first example of an overtly racist immigration law passed in the U.S. In contrast, it represented an open borders policy for white immigrants from Europe. This policy remained in effect until the Immigration Act of 1924 and the Quota Act of 1921. Since the act was passed, we’ve seen multiple laws enacted that deny travel, citizenship, and fundamental rights to people from majority Muslim countries, as well as to nations the U.S. considers an “enemy” for charting their path of independence, such as Iran, Nicaragua, Cuba, and Venezuela.

Although the Chinese Exclusion Act is the first example of racist immigration law in the U.S., one could argue that denying citizenship to everyone, specifically to people of color, intentionally to maximize profit, is the initial act of a racist system and a racist government body that maintains that status quo.

A War From the Depths of Time

Our social progress can be traced to the expansion of democratic rights for the working class through social movements. When people are organized, they can demand what is rightfully theirs, and social pressure compels the government to enact laws that reflect those demands. This has led to significant achievements, including the eight-hour workday, social security, the Voting Rights Act, the Civil Rights Act, and many more.

The same is true for our immigration laws, which offer some hope to our undocumented community by allowing them to no longer live in the shadows when laws are enacted in their favor.

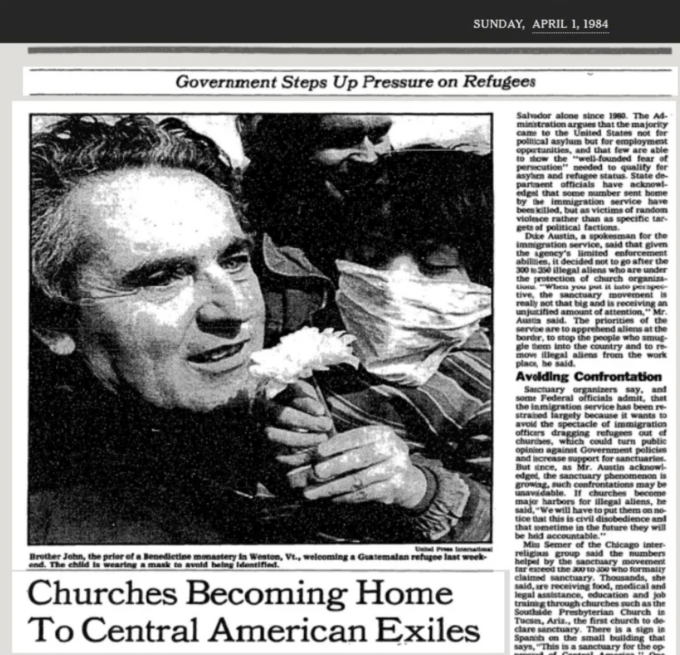

In the 1980s, the sanctuary city movement started as a campaign to offer refuge and protection to Central American refugees fleeing U.S.-supported civil wars that aimed to crush national liberation efforts, mainly led by Marxist groups. However, U.S. immigration policies denied asylum to those fleeing violence. Over one million people from Central America migrated to the U.S.

New York Times coverage of the Sanctuary movement in the 1980s, when refugees were fleeing violence in Central America orchestrated by the Reagan Administration // Source: NYT archives, April 1, 1984

The sanctuary city movement, led by churches, faith-based organizations, and synagogues, formed the “sacred resistance” that turned places of worship into sanctuaries for Salvadoran and Guatemalan asylum seekers, defying federal authorities to promote humanitarian aid, legal reform, and an end to U.S. intervention in Central America.

The sanctuary city movement and other forms of protest compelled the Reagan administration, which was not an advocate for immigrant rights, to sign the Immigration Reform and Control Act of 1986 (IRCA). Ultimately, over two million people were approved for permanent residence.

In the 1990s, people mobilized against Prop 187, known as the “Save Our State” bill on California’s ballot, which aimed to deny public services like education, healthcare, and social services to undocumented immigrants. The bill also included a requirement that public officials, including healthcare professionals and teachers, report suspected undocumented individuals to immigration authorities.

The bill passed with 58.92% of the vote; however, it was challenged in court and subsequently voided due to legal issues, primarily because of public outcry, as thousands took to the streets of Los Angeles on October 16, 1994.

October 16, 1994: Thousands march down Cesar Chavez Avenue near downtown Los Angeles, denouncing Proposition 187, which denies services to immigrants // Source: LAist.com

The same can be said about Obama’s decision to sign the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) on June 15, 2012. DACA provided temporary protection from deportation and allowed eligible undocumented immigrants who arrived in the U.S. as children to apply for work permits and attend school.

This decision followed constant protests by immigrant rights activists against Obama’s deportation policies and his failure to pass the DREAM Act, which offered a pathway to citizenship, unlike DACA, which gives immigrants temporary protection and is revocable. Obama was called the “Deporter-In-Chief” for deporting (removals) over two million people, more than any other president before him.

The protest persisted after DACA was signed.

In Los Angeles, the city saw one of the largest immigrant rights marches on May 1, 2006, International Workers Day, where between one and two million people marched downtown in response to The Border Protection, Anti-Terrorism, and Illegal Immigration Control Act of 2005, also known as the “Sensenbrenner Bill,” for its sponsor in the House of Representative Jim Sensenbrenner from Wisconsin. The march was also called “Day Without an Immigrant.”

That movement continued in 2010 when thousands of people gathered in Arizona to oppose Senate Bill 1070. SB1070 required police to verify the immigration status of anyone they stopped and suspected of being in the country illegally.

Los Angeles has long been a leader in the immigrant rights movement, and it continues to lead today. In Trump’s first months in office, we saw high school students walk out of school to protest his immigration policies. Also, in the last thirty days, LA has been occupied by the National Guard, Marines, and Federal/ICE/CBP agents kidnapping our relatives, and people are protesting their presence everywhere they appear.

It’s always the social movements of the people when they come together under a common struggle against a shared enemy, where the politics are sharp; it’s that movement that can bring about radical change to society. Today, millions of people are witnessing that no government institution is stepping up to protect and defend our undocumented community.

Local police protect federal agents as they kidnap our neighbors, while the Democratic Party does nothing. Meanwhile, both parties fully support a live-streamed genocide in Gaza and tell us that Palestinian lives don’t matter. How can we ever think they care about our families?

It is the people risking their lives against oppressive state forces who are driving change. Today’s activists and organizers are charting a new path of revolutionary optimism, in the belly of the beast.

True comprehensive immigration reform and equality for immigrants can be achieved through shared struggle in the streets. It is not the Democrats or the Republicans that are going to save us. Rejecting both bourgeois political parties and building an independent pro-immigrant rights movement interconnected with other social movements can create the change we need.

This piece first appeared on Abraham Márquez’s Substack.

The post Trump’s Immigration Policy Falls in Line with Racist U.S. History Towards Immigrants appeared first on CounterPunch.org.