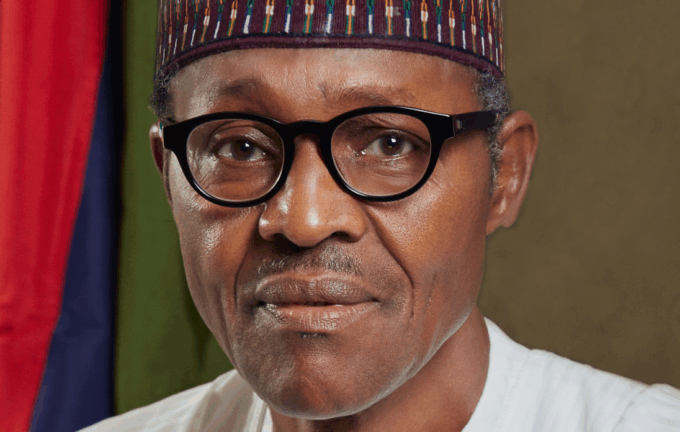

Muhammadu Buhari, Wikipedia.

This article summarizes historian Samuel Fury Childs Daly’s perspectives on Nigerian history and the armed rule that shaped its national identity and government. In particular, I discuss the legacy of the recently deceased Muhammadu Buhari (1942-2025), who saw a transition from military dictator to democratically elected leader. His career marked the rise of the strongman in postcolonial Africa. Also discussed are pivotal events like the War Against Indiscipline and the #EndSARS protests. These incidents showed the strains between repression and democratic freedoms found in Nigeria.

Not as widely covered in the news perhaps but explained by policy expert Mouin Rabbani, was Buhari’s probable cooperation with Israel during the infamous kidnapping and Dikko Affair. No matter the extent of Buhari’s involvement, this event further illustrated how militarism extended beyond its borders into international politics. The president’s influence demonstrated how armed governance remained a powerful force in the world.

Previously in African Politics is Invisible to the Wider World, Daly explained to CounterPunch how the soldier regime became a central political ideology in Nigeria following British colonial rule. Based on court records and personal archives in Soldier’s Paradise: Militarism in Africa After Empire, he argued that like capitalism or communism, the nation offered a structured vision for society, rooted in discipline rather than liberation.

Daly pointed out how the country’s long history of dictatorial rule (1966-1999) created a legacy for its own legal, social, and cultural fabric. Emphases on clothing heightened during times when Nigerians rejected or resisted martial governance. It influenced everything from public respect for uniforms to patterns of internal and external migration. Regarding forced migration, he stated:

This era saw many people deciding to leave Nigeria altogether. It was in the era of military rule that Nigeria’s modern diaspora really emerged. It was only really under military rule when large numbers of Nigerians left permanently. And the large Nigerian communities in the United States, in places like Atlanta and Houston, really emerged during this era. So, this points to something important, which is that not everyone was onboard with militarism as an ideology.

In other words, Buhari was a key figure during this era that drove away many into the diaspora; his rule exposed a kind of militarism that forced migration and created intense ideological opposition among the people.

Muhammadu Buhari

Since Buhari’s death on July 13, 2025, debates about his impact have resurfaced across Nigeria and the world. He first seized power in a 1983 military coup and later returned democratically elected in 2015. He represented military rule’s favorability in postcolonial Africa. To better understand how he shaped political culture rooted in armed governance, I asked Daly for further commentary on the general’s life based on the topics discussed in his recent book.

He reflected on the former president’s career and explained what it exposed about the entrenchment of martial values in Nigeria’s political imagination. He also commented on the tensions between discipline and democracy, and the contested image of the soldier-statesman in the postcolonial world.

Buhari’s political tenure summarized the draw to hard power in a decolonized Africa, a theme readily explored by Daly in Soldier’s Paradise. He called him the “paradigmatic soldier-king,” and described his brief but consequential rule in the 1980s as “an attempt to reinvent Nigeria from the ground up, to remake the country in the image of the army.” He asserted that Buhari truly believed that “military-style discipline could make Nigeria a richer, safer, and more honorable place, and he tried to turn everyone into something like a soldier, that project failed,” Daly stated, “but it also left a lasting mark.” Even when the president returned as a civilian leader, he noted to me that “[Buhari] still had his faith in discipline as a political tool.”

While conducting research, Daly was questioned for wearing a yellow soccer shirt in Nigeria, something not permitted by civilians. What interested me most was his explanation of how uniforms and the regime carried symbolic power and impacted human rights. But at the same time, in moments of crisis, “people are often receptive to leaders who promise order and security,” and Buhari’s “War Against Indiscipline” campaign was clearly designed to deliver that, indicated Daly. The program vowed to clean up the streets and crack down on corruption. Although it didn’t fully succeed, hope kept people committed to it. He pointed out how, “people still preferred democracy, but they were willing to make certain concessions to tyranny if they felt it might make life more secure in the day to day.” That pressure helped to explain how Nigeria tipped toward dictatorship.

The #EndSARS protests in 2020 also brought the divides between structure and freedom into sharper focus. Daly was clear that Buhari “wasn’t well equipped to deal with dissent,” and “he wasn’t very tolerant of dissent, even if that dissent was peaceful.” The violent response to peaceful protests showed that, “he was still attached to the kinds of repressive political methods he used in the 1980s, old habits die hard,” said Daly.

Finally, although Buhari’s legacy is complicated, it says a lot about how militarism still resonates in African politics today. Daly stated, “many people in Nigeria remember Buhari fondly,” even though his campaigns of order mostly failed and his democratic record was mixed. What people hold on to, he further argued is “the promise of order, and the possibility that Nigeria might become something better, better managed, better organized, with a powerful economy to match its vast population.”

That pledge, made by the general and many others, explains why the armed state “still has defenders in African politics today, even though it probably shouldn’t,” he stated. This helped me make sense of why power continued to exercise influence long after its failures were made clear by history. Buhari signified “praise and pain.”

The Dikko Affair

The sharp geopolitical analyst and commentator Mouin Rabbani recently created a thread on X that emphasized Buhari’s impact and The Dikko Affair. He described the event as a dramatic episode within the country’s history and during the late president’s autocratic phase of the mid-80s. It involved an attempted kidnapping of Umaru Dikko (1936-2014), a former minister and outspoken critic of Buhari’s government who was living in exile at the time in the UK. They attempted to mail him inside a crate.

Rabbani explained how on December 31, 1983, Buhari and fellow officers overthrew the country’s elected president Shehu Shagari (1925-2018) and detained many former officials including Dikko, Shagari’s brother-in-law and former Minister of Transportation. Accused of embezzlement, Dikko fled to London where he became an enemy of the new regime.

The author stressed that although Nigeria had no formal diplomatic ties with Israel, the two countries maintained covert relations exchanging oil and weapons. Seeking to bring Dikko back, Nigerian officials requested Mossad’s help. The Israeli intelligence agency devised a plan with Nigerian operatives to kidnap, drug and smuggle Dikko back home in a “diplomatic crate.” The plan involved Levie-Ari Shapiro, an Israeli anesthesiologist to sedate Dikko, explained Rabbani.

On July 4, 1984, Dikko was kidnapped outside his London home but his secretary witnessed the abduction and alerted the police. The kidnappers, failing to label the crates as diplomatic property were stopped at Stansted Airport where customs officers stood on high alert, asserted the author. They legally opened the crates. Dikko, unconscious but alive, was rescued and four conspirators including Shapiro were arrested.

Both the Nigerian and Israeli governments denied involvement, but the UK responded by expelling Nigeria’s ambassador and cutting diplomatic ties. While Israel escaped immediate punishment, a later 1987 assassination of Palestinian cartoonist Naji al-Ali in London linked to Israeli agents provoked a harsher response, outlined Rabbani. Further, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher expelled Israeli diplomats and shut down Mossad’s London station signaling Britain would no longer tolerate covert operations domestically. This incident marked a low point in “Nigerian-Anglo relations” and exposed the dangers of state-sponsored illegal actions abroad, the author indicated.

In essence, the late president used Israel politically and vice versa in a quid pro quo. Although Nigeria did not enjoy legitimate forms of interdependence with Israel at the time, the Nigerian government leveraged Israeli intelligence and military forces to attempt the politically motivated operation. Israel, not unaccustomed to disproportionate involvement, provided expertise, logistical support, and assistance in locating Dikko abroad, which was crucial somehow for the president’s regime; all to neutralize a political opponent living overseas.

This incident of “invasion diplomacy” showed how Buhari’s military government used hidden international channels, including networks with the Holy State, as tools for political repression and maintaining control. The plot left behind a notorious example of the country’s military regime and willingness to engage in secretive state action against its critics with the assistance of other like-minded and militaristic “democratic” partners.

The operation was perhaps one of the most brazen moments of Buhari’s early rule. It exposed the ruthlessness of his regime. And as Rabbani summarized, the covert episode was less about justice and more about political expediency. Although it temporarily enhanced his domestic legitimacy by reinforcing his image as an anti-corruption advocate, Nigeria’s operation was ultimately a demonstration of unscrupulous hard power and not decency.

Whether cracking down on protesters in the twenty-first century, or collaborating with Israeli intelligence to abduct a political opponent in exile in the twentieth, Buhari’s government showed its readiness to bypass legal norms to suppress dissent — in a soldier’s paradise where old habits die hard. The failed affair that Dikko survived wasn’t about anti-corruption initiatives but consolidating authority. Strongmen like to send chilling messages to international critics and as much as Buhari tried to guide a decolonized Nigeria, he prioritized power over democracy.

Notes & Further Reading

Akinsanya, Adeoye. “The Dikko Affair and Anglo-Nigerian Relations.” The International and Comparative Law Quarterly, vol. 34, no. 3, July 1985, pp. 602–616.

“British Custom Officials Open a Pandora’s Crate.” The New York Times, July 8, 1984.

Daly, Samuel Fury Childs. Soldier’s Paradise: Militarism in Africa after Empire. Duke University Press, 2024.

Opalo, Ken. “Soldier’s Paradise: Militarism in Africa After Empire.” Foreign Affairs, May/June 2025.

Rabbani, Mouin. “A Nigerian-Israeli Kidnap Plot in London: Recalling a 1980s Failed Attempt by Nigerian and Israeli Intelligence to Kidnap a Former Nigerian Minister in London and Transport Him to Lagos as Privileged Diplomatic Property.” Substack, July 13, 2025.

Thomas, Jo. “Britain Charges Three Israelis and Nigerian in Kidnapping of Exile.” New York Times, July 11, 1984.

Thomas, Jo. “British Seek Four More in Kidnapping of Nigerian.” New York Times, July 12, 1984.

Weber, Bruce. “Umaru Dikko, Ex‑Nigerian Official Who Was Almost Kidnapped, Dies.” New York Times, July 8, 2014.

The post Muhammadu Buhari and the Soldier’s Paradise appeared first on CounterPunch.org.