Fear of killer robots has obscured a deeper shift in warfare: The fetish of automation masks the commodification of combat judgment. Corporate software reshapes war while preserving just enough procedural “human control” to deflect responsibility.

Review of AI, Automation, and War: The Rise of a Military-Tech Complex by Anthony King (Princeton University Press, 2025).

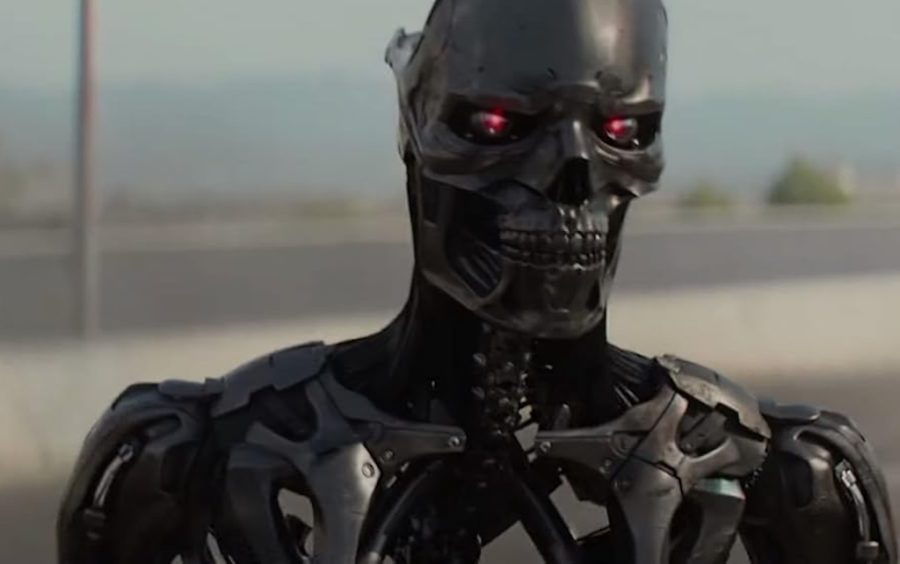

For far too long, two specters have been haunting the world of artificial intelligence and warfare, and they both featured in the same movie. The first is Skynet — the specter of general artificial intelligence achieving consciousness and turning against its creators. The second is the Terminator itself — the anthropomorphized killing machine that has dominated our collective imagination about automated warfare. These twin phantoms have served as convenient distractions while a more prosaic but equally revolutionary transformation has unfolded: the gradual automation of the broader organizational and operational structures of the military through the merger of Silicon Valley and the military-industrial complex.

Anthony King’s AI, Automation, and War is sociology that reads like an illuminating intelligence briefing, rich in description and light on both jargon and normative positions. It is based on interviews with 123 insiders across the developing US, UK, and Israeli tech-military complex. His analysis seeks to demystify some of the most egregious forms of “AI fetishism,” while shifting the focus to actual developments and their influence on the social arrangements of war.

His argument is clear: The fears (and hopes) of full autonomy are misplaced. AI is not “replacing humans.” Nor is the idea of human-machine teaming — which places weapons or systems on an equal footing with human agents — accurate. What we are seeing instead are decision-support systems: tools, if transformational ones, that enable planning, targeting, and cyber operations. Such tools are and will be “used primarily to improve military understanding and intelligence.” In the process, civil-military relationships are changing.

King is right to shift the focus of the discussion away from the apocalyptic fetish of killer robots and superintelligence. His account is descriptively rich. And yet, both his central distinction and overall argument should be subject to some skepticism. It is not clear where support and “empowerment” end and the loss of human agency begins. What is becoming increasingly clear is the convergence of automation across military decision-making structures and the deepening of corporate involvement in war — and that each is animated by similar fetishes.

The Map and the Territory

As in early modern Europe, when the revolution in military cartography transformed how armies understood terrain and planned campaigns, today’s technological tools are revolutionizing how militaries process information, identify targets, and coordinate operations. This is primarily a software revolution, but it does include the integration and coordination of hardware, especially the tools that link surveillance to targeting. Unlike the dreams of “Good Old Fashioned AI” from the beginnings of the field in the 1950s, we are not dealing with a single symbolic map representing all of reality. Instead, the merging of the territory of war with its representation in software is increasingly pursued not through all-purpose general models, but through applied and bespoke applications — a shift that requires the growing integration of civilian tech actors with the military.

Functionally, the revolution is one of intelligence gathering, analysis, and the automation of decision-making cycles, up to and including the “kill chain.” Data aggregators and predictive algorithms connect information gathered by sensors to classification parameters to produce action points. The presence of humans in the overall decision-making cycles and their contribution to specific decision points is constantly reassessed. From planning, to the identification of potential targets, to the decision to engage, human judgment is being systematically “aided” or “enhanced” — some, though not King, may say “replaced” — by algorithmic processes. The human remains in the proverbial loop. But the nature of this loop is changing. And that change is twofold: automation is spreading, and so too is the ever-deeper participation of the civilian tech sector.

How did we get here? As with so much at this stage of late and extreme technocapitalism, the present situation is both an evolution of, and a leap beyond, the military-industrial past. The capacity to survey and militarily engage potential “threats” across the globe has been the goal of the US military-technology apparatus for the last century. As General William Westmoreland put it during the Vietnam War: “On the battlefield of the future, enemy forces will be located, tracked, and targeted almost instantaneously through the use of data links, computer assisted intelligence evaluation, and automated fire control.”

This goal has been served consistently by the business operating on the West Coast of the United States, as vividly described in Malcolm Harris’s Palo Alto. And this is the message — and the tradition — driven home, if in tortured, convoluted, and hollow ways, in Palantir CEO Alex Karp’s recent manifesto, The Technological Republic. Technological capitalism’s purpose and obligation, alongside profit-making, is in the service of the military domination of the world by “the West.”

The appearance and trajectory of Palantir Technologies can be read as the central case study in this latest stage of corporate-military evolution. It is by now a familiar story. Founded by Peter Thiel and Karp, Palantir was explicitly designed as a national security company from its inception. Post-9/11, the skies of those subject to the War on Terror were dominated by drones gathering surveillance and increasingly conducting targeted assassinations. However, even though Palantir was from the very beginning supported by members of the military and intelligence establishment, it initially struggled to penetrate traditional military procurement processes, before finding its opening by working with Special Forces units frustrated with constraints on their operational tempo and lethality.

The Palantir Paradigm

It wasn’t robots but logistical solutions that Palantir offered: the dynamic aggregation and analysis of the vast amounts of data generated by military sensors, satellites, and open-source intelligence, tailored for active operations. Their ambition — now largely realized — was to become the nervous system connecting unlimited surveillance with targeting, operating across conflicts and alliances, while at the same time collapsing the line between warfare and increasingly securitized domestic politics, most notably immigration, policing, and health care.

A key turning point in the establishment of this model was the Pentagon’s Project Maven, an ambitious effort to use machine learning to analyze the terabytes of video footage generated by years of drone operations. Initially partnering with Google, the project aimed to automate the analysis of surveillance imagery — work that would have otherwise taken human analysts hundreds of thousands of hours. When Google employees famously revolted against military applications of their technology, Palantir stepped in.

King astutely identifies the Google revolt as marking “the beginning of this new golden age of the tech-military complex.” Rather than representing successful resistance to militarization, it merely cleared the field for companies keen on defense work. The result has been the emergence of what might be called “military-native” tech companies — firms like Palantir and Anduril that were designed from the ground up to serve defense markets. They have been proliferating ever since.

One can survey that burgeoning ecosystem by looking at the “American Dynamism 50” list compiled by Andreessen Horowitz, a venture capital firm which has been central to both the financing and the politics of the field. “Peace through strength,” in anticipation of a potential war with China, is the connecting investment rationale, as well as — now — US national security strategy.

At the same time, corporate actors with initially expressed qualms, or who had hitherto maintained a primarily civilian focus, including giants like Google, Microsoft, and Amazon, have been brought around. Project Nimbus — the cloud computing contract between the Israeli government, Google Cloud, and Amazon Web Services, which has played a central role in Israel’s capacity to run the surveillance and targeting operations both in the occupation of the West Bank and the destruction of Gaza — is a case in point. The US army is increasingly relying on SpaceX’s Starlink satellites for command and control, as has, of course, Ukraine, in its defense against Russia.

Israel Is the North Star

The Israeli model shows how ever-increasing integration between tech companies, intelligence services, and military units is seen as the very ideal that this global ecosystem aims to emulate. Some of King’s interviewees criticize the US and UK systems as not living up to the degree of functional integration achieved in Israel or praise them for moving in that direction. The direction is one of broad militarization.

In the Israeli tech-military complex, one Israeli Defense Forces (IDF) source told King, “[s]ome civilians are not really civilians. And some military industries are not really industries.” Netanyahu’s “super-Sparta” comment — his description of Israel as a hypermilitarized, self-reliant tech power — was meant to capture not only an ideal of autarky but also the further deepening of connections and the weakening of barriers between civil and military forces.

This blurring of boundaries is exemplified by companies such as Elbit Systems, which King describes as having “integrated with operational units in the IDF . . . to design, develop, and improve software” in real-time battlefield conditions. At least eighteen American tech corporations are involved in the conflict in Ukraine. While little detail of the specific practices is open to the public, some are providing hands-on assistance through bespoke algorithms on the ground. Palantir has openly claimed it is “responsible for most of the targeting in Ukraine.”

The result is a feedback loop where military operations generate data that improves algorithmic systems, which in turn enable speeding up the “kill chain” and “reducing the cognitive load,” with most of this loop increasingly automated and captured by corporate actors. Such loops are generating a particular type of military procurement. Elke Schwarz has shown how these ever-faster feedback loops fit within a venture capital ethos — moving fast and breaking things — with what VC investor Reid Hoffman has called “blitzscaling.” Indeed, between 2014 and 2023, the value of defense sector venture capital deals grew eightfold.

Speed, volume, transformation, and integration now constitute a new form of dynamic mapmaking, altering both war and civil-military relationships. Such developments are deliberate, celebrated, and openly recognized. In June 2024, senior executives from Palantir, Meta, and OpenAI were formally commissioned as Army Reserve Lieutenant Colonels and senior advisers as part of the Army’s Executive Innovation Corps — a visible symbol of how thoroughly Silicon Valley has penetrated Pentagon leadership. The US Department of Defense’s Defense Innovation Unit is headquartered in Silicon Valley, dedicated to accelerating the adoption of commercial and dual-use technologies, and staffed by individuals with extensive connections to the tech sector.

The Full Autonomy Fetish

Can we, then, talk about the automation of war as the replacement of political judgement by algorithms? Or is what is happening fundamentally different? King thinks so and tries to draw a clear distinction between fully autonomous weapons and the decision-support systems that increasingly dominate the battlefield. In demystifying the promise of full automation and the far-fetched ideas of artificial (general) intelligence in war-fighting, he applies Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism to military AI systems. Just as commodities obscure the social relations of production that create them, AI-powered military systems obscure the organizational choices and human decisions embedded in their algorithms. A targeting recommendation generated by an AI system appears as an objective, technical assessment rather than the product of specific political and military priorities programmed by human designers.

Indeed, to simplify a long line of interdisciplinary critique and connect it with common sense, artificial intelligence is not real intelligence. To argue otherwise is mystification. And, in war, such mystification serves multiple functions. It provides political cover for controversial targeting decisions — after all, the algorithm, unclouded by hate, recommended it. It creates distance between the end result and those that set the parameters that led to it, weakening both moral and legal accountability. And it obscures the growing influence of private corporations over life-and-death military decisions.

Those opposed to fully autonomous weapons have long argued that, even if there is functional equivalence between humans and machines in cognitive and kinetic capabilities, artificial systems lack the moral agency necessary for them to be responsible participants in war. A taboo on fully autonomous weapons is barely holding, with the UN General Assembly Resolutions upholding it appearing increasingly precarious and subject to crucial holdouts.

King argues that the developments he is describing — the mapmaking, the bespoke tools, the functional merging of tech and war-fighting — are very different from the promise and specter of full autonomy. Such decision-support systems maintain the taboo against full autonomy and maintain human — political and military — agency and judgement, from the planning to the operational phases. Instead, they revolutionize the application of that agency, as well as the social structure of war-fighting. According to this view, both the enthusiasts and the doomsayers have been wrong: the ultimate commodification of human thought through the specter of general intelligence and full automation has been a red herring.

The Loop Is Changing

And yet, such red herrings have served a function. While humans have remained, precariously, in or on the proverbial loop, the loop has changed in ways that evoke familiar Marxian concepts of alienation, commodification, and fetishism — not just of the commodity form but of the corporate form as well. Keeping the specter of full autonomy at bay, if only just, has allowed a deeper and more pervasive automation of war across both routine and critical military functions, with ultimately quite similar effects in terms of the loss of political agency and judgement in the conduct of war. In addition, we may be moving toward an even deeper type of technological commodification, one that spreads and totalizes war across the civil-military divide.

The examples of the tools used for the destruction of Gaza are instructive. The two central tools, Lavender and Gospel, are data aggregators, operating on preset parameters and generating predictions, classifying humans and objects as proposed targets. There are, of course, key elements that clearly reflect human political and moral — and legally significant — judgement: the broad nature of the classifications; the extraordinarily permissive collateral damage parameters; the combination of the target classification with the disturbingly named Where’s Daddy tool that prioritizes the targeting of suspected fighters at their personal homes and with their families; and the use of these tools, including through the prioritization of volume of targets requested, in a campaign of total destruction.

At the same time, it is also quite clear from the relevant reporting that human agency is being reduced, at least at the mid- and lower-operational level — especially where the priorities of volume and speed in physical destruction and killing leave little space for human intervention or make it easier for human operators to live with the results. It may be that blind approval of all proposed male targets within a twenty second window reflects some minimal form of judgement, but it is, at best, judgement reduced to participation in a broader, increasingly automated system.

In assessing the continuing existence of human agency, it is important to understand the extent to which individuals at all relevant points in a targeting cycle meaningfully engage with the application of core legal principles: distinctions between civilians and combatants, and between civilian objects and military objectives; proportionality in the infliction of incidental civilian harm; and the obligation to take all feasible precautions in attacks to determine the nature of the target and minimize civilian harm, as required by the law of war. These requirements demand the exercise of cognitive agency, discretion, and judgement — both to balance military necessity with humanitarian protection and because the law is a human creation, irreducible to code, aimed at governing relations between human beings in the world, even a world at war.

Whether a given technological system, given its classification parameters, is capable of drawing the relevant distinctions required by law, both at the level of sensing and accurately recognizing and classifying a target and at the point of engagement, is still very much an open question. Increasingly, that question is being sidelined by technological and institutional developments. Even with the increasing sophistication of sensing, data analysis, and the synthetic representation of reality to users, an assessment will require situated judgment and not the near-blind following of a recommendation.

Whether, for example, a building by “nature, location, purpose or use make an effective contribution to military action and whose total or partial destruction, capture or neutralization, in the circumstances ruling at the time, offers a definite military advantage,” as required by treaty law, cannot be determined by the automatic ping of a mobile signal associated with an individual algorithmically ranked as a potential militant. This is not only because of the unacceptable margin for error, or because such an approach reflects an overly broad and permissive interpretation of the term “use.” It is primarily because decisions that lead to death and destruction are — and should always remain — human responsibilities. Unless, of course, the priority is the rubber-stamping of indiscriminate destruction.

The phrase “meaningful human control” has been promoted over the last decade in order to try to draw a line beyond which automation of a given system shouldn’t cross. It is a vague and imperfect phrase, which has proven unable so far to stem the tide. The spread of these technologies throughout the targeting cycle is rendering it increasingly hollow. More recently, the concept of “context-appropriate human judgement and control” has been advanced; wordier, perhaps more textured, but it, too, risks being an empty shell.

The Mutual Capture Between War and Capitalism

Where is the line between decision support and full automation — the line we should not cross? Consider three factors:

First, key exercises of discretion and judgement in the identification of specific targets and their engagement are being commodified. They increasingly appear as abstract values churned out by automated systems on the basis of set parameters. Those parameters may be scrupulous in their claimed adherence to legal rules or, as in the IDF case, extremely permissive, to put it mildly. But in both cases classification is automated, abstracted, commodified, dehumanized.

Second, there is a reduction of human agency. This reduction may be not absolute. It may still be possible to regard those who set the parameters, deploy the weapons, activate the system, or provide final approval as, to some extent, responsible. In certain circumstances, as King’s interviewees occasionally argue, participants may perceive the technology as providing richer informational inputs that benefit the exercise of judgement and agency. And yet, at the same time, the gradual automation of the targeting cycle inevitably saps agency — removing the participants from the cognitive and moral costs of war. This is especially true where speed and volume are overriding priorities. As in Gaza, such speed and volume may be serving the goal of indiscriminate and comprehensive destruction. But even in conflicts where annihilation is not the wave that carries all human judgement, there is a point at which it is simply not possible for human beings to exercise agency over the volume of information that machines are able to process — where bespoke interactive tools are effectively taking their human users for a ride. In this context, any potential objections to the adoption of AI tools and their recommendations, whether at the operational or broader social and political level, are becoming increasingly weak.

Finally, there is a crucial third factor which is, I think, less clearly understood. What, for our purposes, is the relationship between commodity and corporate form? What is the relationship between, on the one hand, a political, military, or legal judgement that is commodified through algorithmic mystification and, on the other, the increasing involvement, influence, and even capture of war-fighting by profit-maximizing corporations? Does the latter, by its nature, advance the former?

King thinks not, hence his distinction between full autonomy and decision-support technologies developed by the emerging tech-military complex. He argues that the shifting civil-military relationship requires our attention but does not necessarily entail loss of agency — and, indeed, that its technological expression is currently “empowering” decision makers. We have seen however, that at least with respect to the demands imposed by the law of war, agency is in fact being lost. Still, perhaps there’s no necessary connection. Perhaps power and judgement over war-making are shifting toward corporate actors within the growing complex of hypercapitalism and militarism. And perhaps the corporate promotion of the gradual automation of the decision-making loop is fundamentally opportunistic — a “disruption” facilitating capture — and only happens to coincide with the commodification of judgement and loss of agency.

But there are grounds to be skeptical. The very logic of capitalism and its associational forms are geared to promoting moral distance and structures of irresponsibility. The loss of agency through automation serves that very same function. The fueling of war by the profit motive is, of course, as ancient as war itself, but a sociology of this tech-military complex may yet show how the breakdown of barriers through militant hypercapitalism connects the commodification of AI to the commodification of the social organization of wart-fighting

In the meantime, the actual killer robots — potentially fully autonomous “unmanned systems” — are very much in development, testing, and partial deployment. The mutual capture of militant hypercapitalism and the national security state is preparing us to welcome them as equals.